Boston Conservatory Celebrates Women’s History Month with Nod to Founder Julius Eichberg’s Work for Gender Equality

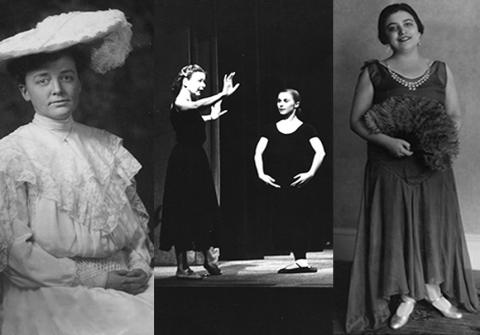

Left to right: Lillian Shattuck (courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University); Ruth Ambrose instructing a student; Iride Pilla.

As the nation recognizes Women’s History Month this March, Boston Conservatory at Berklee salutes the legacy of visionary founder Julius Eichberg, who in 1867 opened the Conservatory’s doors to women and those who had never before had access to a conservatory-style education.

Boston Conservatory’s present-day reputation for training women as performing artists, educators, and industry innovators is rooted in Eichberg’s work. When he founded the Conservatory, Eichberg embarked on what was considered at the time to be an unconventional—perhaps even radical—initiative: to have as many women in his music training program as men, according to the school’s original catalogs and newspaper advertisements of the day.

Boston Conservatory counts the following women among its many alumnae who made an impact in the arts: acclaimed violinist Lillian Shattuck; two-time Grammy Award–winning opera legend Lorraine Hunt Lieberson; television star Katharine McPhee of the CBS drama Scorpion; dancer Ebony Williams, a Roxbury native who became a member of the Cedar Lake Dance Company and was one of the three featured dancers in Beyoncé’s hit music video Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It); opera star Victoria Livengood; classical guitarist Lily Afshar; musician and author Elizabeth Borton de Treviño, who won the Newbery Medal in 1966 for her book, I, Juan de Pareja; Broadway performers Erin Davie, Hayley Podschun, Stephanie Umoh, Alysha Umphress, and Nikki Snelson; and actress Keesha Sharp, best known for her long-running role on the show Girlfriends.

“We are justifiably proud of many aspects of the Conservatory’s legacy, but we take special pride in our history of training and supporting women in their pursuit of working as musicians and training as artists and teachers of the highest caliber,” said Boston Conservatory at Berklee President Richard Ortner. “We were ahead of our time.”

Boston Conservatory quickly became known for training and educating students regardless of social status, culture, or ethnicity. Himself a German immigrant, Eichberg sought to empower those who struggled, and supported the artistic aspirations of both women and people of color. The Conservatory’s inclusive approach to education set both Eichberg and Boston Conservatory apart over the decades.

The Conservatory also has a long history of hiring women on its faculty, including Grace DeCarlton, who created the first dance programs at the Conservatory in 1933; Ruth Sandholm Ambrose, a young, talented ballerina who Jan Veen asked to join the faculty for a semester and, ultimately, retired decades later as the Dance Department’s leader; Sue Ronson Levy, best known as a tap dance innovator; and dancer/choreographer Julie Ince Thompson, whose unique work celebrated women’s stories.

This tradition continues today with Cathy Young, dean of dance, renowned performer and master teacher, and a multitude of faculty members including esteemed composer and instructor Marti Epstein, whose work has been performed by the San Francisco Symphony, the Radio Symphony Orchestra of Frankfurt, and members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, to acclaimed percussion/marimba chair Nancy Zeltsman. All three women are considered trailblazers in their respective areas and are committed to mentoring female students to pursue fields that, in the case of music composition and percussion, have been historically led by men.

Eichberg not only believed in educating and training women as musicians—he was also committed to seeing them earn a living as performers. That was his intention in 1879 when Eichberg recruited his most talented female students and founded the Eichberg Quartet (also known as the Eichberg Ladies’ String Quartet or the Eichberg Quartette). It was the first all-female professional string quartet in the world.

In 1881, Eichberg sent the quartet to Berlin for a year of study, where they performed and received positive reviews by local press. In an article titled “Lady Violinists,” Eichberg wrote: “We should be remiss in failing to credit our female students with at least an equal degree of talent, industry and success. We gladly espouse the cause of women’s right to play upon all the instruments of the orchestra.”

Another of Eichberg’s students, violinist Caroline B. Nichols, founded an all-women’s touring orchestra called The Fadettes in 1888. It toured nationally until 1920, employing dozens of Boston female musicians, most of whom studied at the Conservatory.

Ester Ferrabini Jacchia was an internationally acclaimed opera singer when she joined the Conservatory faculty in 1920 at the encouragement of her husband, Agide Jacchia, who left his conducting position with the Boston Pops Orchestra in 1920 to run the Conservatory. When her husband died in 1932, Madame Jacchia assumed leadership of the school, overseeing its management and operation for one year until transferring ownership to alumnus Albert Alphin.

One of Madame Jacchia’s earliest students was Iride Pilla, an opera singer from Lynn, Massachusetts, who would go on to perform on some of Europe’s greatest stages. In what has become a Conservatory tradition, Miss Pilla—as she was called—returned to the Conservatory as a member of the faculty. Pilla, who died in 1997 at the age of 92, taught thousands of students, many of whom continue to perform and teach today.

Eichberg’s work towards gender equality in the arts is one of the many legacies that the Conservatory is celebrating as part of its 150th anniversary year, a milestone that will be formally celebrated on May 9 with an historic gala at Symphony Hall emceed by Tony–award winner and television actor Alan Cumming. As the school nears its gala celebration, it remembers Julius Eichberg’s vision for a conservatory dedicated to training—and elevating—all deserving artists.