A Midsummer Night’s Dream Goes Steampunk (Or Is it Steam-Puck?)

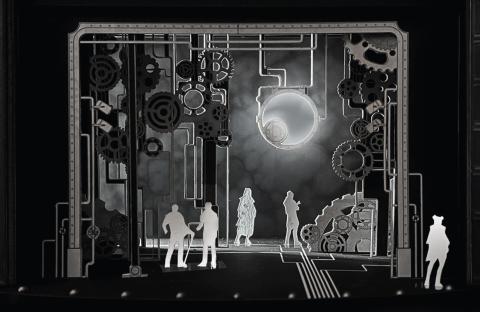

Set designer Evan Adamson’s model for A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Courtesy of the designer

After 400 years and countless stagings, audiences have acquired some preconceived notions about A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Enchanted forests, fairy wings, and donkey ears likely come to mind at the mention of Shakespeare’s play—which the English composer Benjamin Britten crafted into an opera in 1960.

Boston Conservatory’s new production of Britten’s work—selected as part of its spring 2024 Center Stage collection—reimagines the original setting with an all-out steampunk aesthetic, trading the Athenian woods for a mechanical landscape of cog wheels, sprockets, and metal conduit. The costumes, too, defy convention, blending Edwardian-era corsets and exposed hoop skirts with leather moto jackets and glam-rock platform boots.

Coming to the Huntington Theatre April 18 to 21, this new staging establishes a dream-like environment that’s in keeping with Shakespeare’s original play and Britten’s operatic adaptation; but it does so using an entirely different visual vocabulary, says director David Gately, professor of opera. “I was looking for a kind of fantasy world that wasn’t the normal forest and trees that we’ve all seen for A Midsummer Night’s Dream before,” he says. “I thought this was kind of perfect. It put us in a fantasy world that had a modern edge to it, but wasn’t the normal, ‘we’re lost in the forest’ kind of thing.”

Stemming from a subgenre of science fiction, steampunk draws inspiration from Industrial Revolution-era machinery (both real and imagined), and updates the style of that period with an outlandishly punk edge. Steampunk might be an alternate version of history or a nostalgic glimpse of the future, or both. And according to set designer Evan Adamson, its anachronistic quality makes perfect sense for the Conservatory’s new production: a 21st-century staging of a 1960 opera adapted from an Elizabethan play set in ancient Greece.

“The steampunk aesthetic seemed right in that regard, being a cobbled-together visual language with meaning and intricacies,” he says. “It seemed to follow a similar journey as the characters we’re being introduced to in the text.”

Adamson is a longtime collaborator of Gately’s and has worked on design teams for Tony-nominated Broadway productions, including Hedwig and the Angry Inch, The Iceman Cometh, Leopoldstadt, and Matilda, which won the 2013 Tony Award for Best Scenic Design in a Musical. Tasked with creating a steampunk forest, Adamson began the process by asking himself a difficult question.

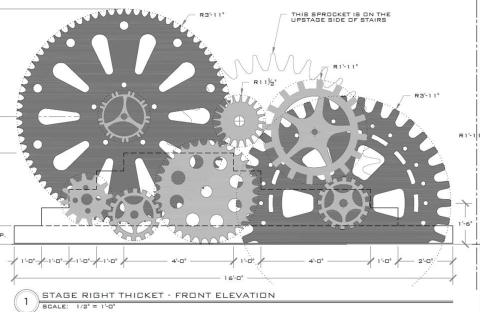

“What does it mean to be a steampunk tree? That’s really where the job begins and the creativity springboards from,” he says. “I looked heavily at the inner workings of clocks—time being a thing that we’re conscious of in the story of Midsummer… and finding within them gears and sprockets, I came up with a response to that, where I crafted foliage and thickets.”

Midsummer’s libretto was adapted by Britten and his partner, Peter Pears, and remains faithful to the original Shakespeare, except that the opera does away with the play’s first act. In Britten’s version, the story begins with an argument between Oberon and Titania, king and queen of the fairies, and the comedic plot unfolds as Oberon dispatches the fairy Puck to cast a spell on his queen. The story’s human characters—what fools these mortals be—wander the woods as if in a dream, lost and at the mercy of the fairies’ magic.

Costume designer Zoë Sundra explored various aspects of steampunk fashion to create distinct wardrobe styles for different categories of characters. Costumes for the human characters look the most recognizably steampunk; while Sundra describes the fairies’ and fairy royals’ outfits as “more like leather, moto, queer, kind of leather bar in P-Town, with a touch of Burning Man…. You’re seeing somebody like Oberon in this floor-length leather fringe coat with studs all over it,” she says. “That’s not practical for forest living, but it’s fabulous!”

The frivolity of steampunk fashion aligns neatly with the opera’s themes and helps bring to life its comedic elements, she adds. “There’s so much that addresses reality and that speaks of what our lived experiences are—and that’s wonderful—but it’s so nice to have the complete opposite.”

Gately says that effective costumes and sets can establish tone immediately and communicate crucial information to the audience before the characters even open their mouths to sing. Over the past few decades, he has stage directed more than 300 productions for dozens of opera companies; and from experience, he has learned that a fresh concept can revitalize the repertoire. Gately is perhaps best known for his spaghetti Western staging of Gaetano Donizetti’s Don Pasquale, which has been mounted by a dozen (and counting) opera companies throughout North America.

“I like playing with setting,” he says. “I don’t like my settings to be on Mars or anything like that. I like to ground them in some sort of reality. But this time I just said, ‘Let’s go full out on this idea.’”

A Midsummer Night’s Dream will be presented at The Huntington Theatre from Thursday, April 18 through Sunday, April 21. Learn more and purchase tickets.